- Home

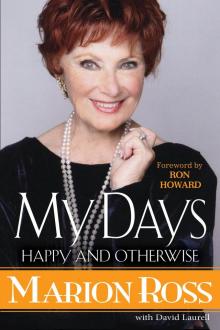

- Marion Ross

My Days Page 14

My Days Read online

Page 14

Chapter 12

My Luckiest Airplane Ride

By the time Ellen had celebrated her first birthday, my marriage was anything but normal or conventional, if, in fact, it could even still be considered a marriage. Effie was constantly coming and going—living at home for stretches and then gone for days or even weeks at a time. When he was at home, there was a lot of arguing and yelling, and whatever help he may have received at the hospital had been washed away with Scotch. He was still working and, to some extent, assisting me financially, if not physically or emotionally, in keeping our household running. I also continued to work, which was becoming more of a stressful situation as I tried to balance my career with the raising of a five-year-old and a toddler on my own.

The chinks in our marriage were clearly evident by this time, but the first real fissure of consequence, which would prove to be a harbinger of what would lead to its end, occurred when I experienced the first loss of my life. During the final years of my father’s life, he lost his hearing and experienced the health issues that come with age. When I received the call that he had died, it was the first time I had experienced the death of someone very close to me.

None of us know how we will deal with a difficult situation, challenges or the loss of a loved one until we actually face those issues, and while I was crushed by the news of his passing, I found myself handling it with a sense of calmness and acceptance. I never really thought about it at the time, and I honestly never really gave it much thought until I began working on this book, but I have always seemed to deal with bad news, even the loss of dear friends, family members and beloved pets, in a very matter-of-fact way. That is not to say I haven’t experienced the horrible pain and deep sadness that come with a loss, but I have always had the capacity to process the news of a death very quickly, accept it, adjust, and move on. I have never been the type to fall into a deep sense of grief over a loss. In fact, I don’t know if I ever really knew how to grieve in the way I have seen others handle a death. I don’t know what gene I may either have or be lacking that makes me that way, but it has always been a part of my makeup—to be pragmatic, keep my chin up, and just deal with whatever needs to be dealt with.

In the case of my father’s death, the thing that needed to be dealt with was to get to San Diego to be with my mother and assist her in the planning of his funeral. I wanted Effie and the children to go with me, and since I just expected Effie to be there for me, I was shocked when he told me he didn’t want to go. We had very young children who needed to be cared for while I tended to all the issues surrounding my father’s death, and Effie’s attitude toward me was cold and uncaring in a way that made it clear to me that whatever love we may have had for each other had deteriorated to a point that it could not be saved.

With my father’s death serving as the impetus for the beginning of the end of our marriage, I did find myself experiencing bouts of depression. It wasn’t a depression that I ever considered to be debilitating in any way, but rather one that left me in a fog of deep disappointment, melancholy and anxiety. I had always felt, from the time when I was very young, that I had the strength to handle things on my own, and yet there was something about the anxious feelings I was experiencing that told me I should seek professional help, and this realization was coupled by the urgings of a few close friends.

Just as the experts at Alcoholics Anonymous relieved me of the guilty confusion I was feeling by explaining that I was powerless to change an alcoholic’s behavior, the psychiatrist I went to see made me feel better when he told me it was completely natural and normal to be feeling the way I did.

“There’s nothing crazy about being upset over a crumbling marriage, financial concerns, the fear of losing your home, and the well-being of your children,” he told me. “If you weren’t feeling anxious and depressed over these things, then you would really have a problem.”

While Effie and I didn’t formally divorce until 1969, our marriage and life together had been over for years before that. When we did officially separate, the children were old enough to understand what was happening to some extent and took it hard. We all did. They continued to live with me in Tarzana but did go and stay with him at times. When they would return from spending time with him, they would say that he had told them he loved me and wanted to come back and live with us again. At one point, after the children returned and pleaded with me to let him come back, we did try a brief but ill-fated reconciliation. After that, we both knew it was really over, and Effie and I sat down and talked about it like civilized people. I got the impression that even though our marriage was over, Effie was in no hurry to make it final. I knew if I let it linger on, it would just keep both of us and the children in a state of limbo, which I didn’t want to put any of us through. And so, just as with everything else that happened throughout our marriage, I was the one who had to take the initiative, contact an attorney, and handle the arrangements that would bring the marriage to an end.

In the weeks and months following our divorce, I began taking more jobs than I had in some time and felt confident that I would be able to continue to support myself and the children without Effie’s help. I even rented out a room in our home to a college girl for sixty-five dollars a month to help me get by.

It was a time of strange emotions for me. On some days I had that springlike feeling of renewal many people experience following a divorce. I felt as if I was at the beginning of a new chapter of my life that could be exciting and rewarding. And yet there were also days when I couldn’t get over the mess I had gotten myself into. On those days I cried a lot and felt like such a failure. Divorce, for anyone, brings with it the knowledge that you were a tremendous failure at something that should have been your highest priority to make work.

I had wanted my marriage to work. I had wanted us to be a family like the ones I did parts in on shows like Father Knows Best. And I had wanted to have succeeded at making my dream—the one I had been so dedicated to from the time I was a child—a reality. All those things had been very important to me, and yet here I was, no Mrs. Hotshot, no Mrs. Big Shot or Mrs. Big-Time Actress. In fact, I wasn’t even a “Mrs.” at all anymore. I had failed at two of the things that had been the most important to me: my career and my marriage. This nagging sense of failure soon saw the bad days overtake the good ones, and had it not been for the love of my children and my dedication to them and their care, I think that psychiatrist I had gone to see would have reversed his analysis about my not being crazy.

While it was a very difficult time for me, I did everything I could to shield my despondency from my children, the people I worked with, and just about everyone I encountered, other than a few close friends. I began going to church a lot and immersed myself in reading the Bible. I really felt I was finding strength and hope in various scriptures, and I embraced Christianity in a very personal and deeply spiritual way. That really began one Sunday, after coming home from church. I was feeling down and hoped I could soak away some of my blues by taking a nice hot bath. As I slipped into the tub and let the water envelope me, I became extremely emotional and started crying uncontrollably. I remember lifting my hands upward and saying, “I give up, God. I can’t do this anymore. I repent.” I just kept saying it over and over until I cried myself out.

During this time, I saw my sister more than I had in many years, and we often talked about our faith and religion. She was, however, the only one I talked to about my faith. I didn’t want anyone else to look at me as one of those people who, after hitting rock bottom, finds Jesus and constantly reads the Bible and prays. But, during that time, that was very much who I was.

I was trying to do all I could to lead a Christian life. I was tithing my income, even when it was derived from an unemployment check, and I thanked God for my children and for the gift I believe He had given me to perform. Now all I needed was for something to break for me to be able to share that gift in the way I had always hoped to. I was tired of feeling like a failure, of

constantly struggling, of worrying as each job ended when the next one would come, and of wondering if I would ever get the opportunity to, if not realize my dream, at least feel as if I was successfully accomplishing something—anything.

We have all read or heard the inspiring stories of people who have turned their lives around and overcome great disappointments, setbacks and failures. Many of those stories include grand moments of awakening—dramatic epiphanies in which lightning bolt strikes provide clear intuitive perception and insights. My moment—the one that shook me out of my depression—wasn’t quite so monumental. In fact, it simply took place one afternoon, as I sat at my kitchen table, aimlessly staring at the floor.

Maybe the piece of linoleum that caught my eye had just broken, or maybe it had been that way for months. I had no idea. But there it was, sticking up in a curl that made it look like it was staring back at me with this big old snarling evil grin. I knew we had some leftover linoleum out in the garage, and after rummaging through a few things, I came upon a nice big square of it. I went back in the house, cut the big old snarling grin away, cut the new piece to fit the area to be replaced, heated it up in the oven, slathered it with glue, and pushed it into place.

Maybe I just got lucky when it fit in so perfectly I couldn’t even find the seams, but handling that repair so quickly and adroitly gave me a boost like I hadn’t had in a long time. I stood back to look at my handiwork, and this wave of strength and determination came over me. “Well, well, just look at you,” I said to myself. “Boy, oh boy, you not only fixed it, but you did a great job.”

It wasn’t nailing an audition for a great part, getting cast in a leading role, or stepping out of a limousine and having the crowd yell, “It’s Marion Ross!” but at the moment, it just may as well have been. They don’t give out coveted awards for fixing linoleum floors, but the way I started singing and dancing around my house, you would have thought I had just collected an armful of Oscars, Emmys and Tonys.

It was in that insignificant and mundane moment, inspired by a little piece of curled-up linoleum, that I felt like my old self for the first time in a long time. All right, I thought. I may now be a woman in my early forties with kids in grade school. But I also have a substantial acting résumé, and so why can’t a woman who can so magnificently repair her kitchen floor still realize her dream of becoming a star!

I began making a lot of calls, touching base with my agent and old contacts, letting them know I was very actively seeking work. I even went as far as to hire a press agent to help me shape my career and garner some publicity. When I look back on that time, I have no idea where I came up with the two hundred dollars it cost me to retain her each month, but somehow I did. And it was money well spent.

I began getting calls for various television series and show pilots, but I needed something more to happen than that. I was now the sole breadwinner, and while that was a role I had been accustomed to playing in the past, this time it was different. It was no longer simply providing for my husband and myself and coming up with the rent for a little apartment. I now had to handle the mortgage on an Encino home, along with supporting two children. My life-changing linoleum moment may have gotten me back into the game, but I was still finding myself either sitting on the bench or getting third- or fourth-string roles—neither of which could maintain the lifestyle I was living, much less transform my dream into a reality.

I was out there scrambling, making the rounds, calling everyone I knew, and really hustling for roles. If I got wind that someone was doing a pilot or a film, I did all I could to get in touch with their casting people. One of those people was the writer and producer George Seaton, who was casting for a film he had written and would be directing called Airport, which was based on Arthur Hailey’s 1968 novel of the same name and in time would prove to be the impetus for the “disaster film” genre, which would become so popular throughout the 1970s.

I didn’t know much about the film, except that it would star Burt Lancaster and Dean Martin, that Seaton would be directing it, and that I made the fortunate decision to stop by his office with a résumé and photo. Once I was granted the opportunity to meet with him, it all went much the same way as the hundreds of other similar meetings I had been in with casting people and directors: a quick exchange of pleasantries while being looked over from head to toe and a thirty-second spiel on what I had recently done. The one thing that made this meeting different was the way it ended. Unlike my typical closing spiel of “I’m very grateful for your time,” I instead blurted out, “I’m recently divorced, with two children. I really need this job, and so, please, can I have your card?”

Seaton sat with his mouth open for a second or two and then said, “What do you want my calling card for when it’s a part that you want, right?”

I shook my head in agreement.

“Okay, then,” he continued. “Show up for casting.”

A week or so later, I made my way to the Universal lot, where I had been told to report, and made my way to the soundstage where they were casting for Airport. As I walked into the stage, a wave of nostalgia (and not the good kind) swept over me as I realized it was a “cattle call,” not unlike the one I had experienced at Paramount all those years earlier. There were all these actors just sitting around, waiting for that minute or two in which they hoped to distinguish themselves from the crowd. I hadn’t been on an audition for a part like this in some time, but it was clear to me that nothing had changed. There was that same look on all the actors’ faces, one that every actor knows all too well: the old “I desperately need this part” look. As is always the case with these things, there was very little, if any, small talk as we all just sat there, staring at the stage floor and avoiding eye contact with anyone.

When my turn came, I did all I could to wow them with my newfound linoleum-repair-inspired enthusiasm, subtly shaded with what I hoped was just enough pity-inducing despondency that Seaton would remember me as the pleading divorcée who had kids to feed. In retrospect, I think none of those things meant anything. They were looking for actors with genuine acting chops. My résumé showed that I fit that bill, and soon thereafter, I received a call that included the sweetest four words any actor can ever hear: “You got the part.”

I was thrilled, although my agent, my publicist, some friends and a handful of others, who were all looking out for my best interests, were far less than happy about it.

“You can’t take that part,” I recall someone (if not everyone) telling me. “It’s a nonspeaking extra role that is way beneath what you have been doing.”

Maybe so, I thought (but didn’t ever actually come out and say to anyone), but it’s work—paying work—in a feature film, and I need it.

Yes, it was a nonspeaking role of an airline passenger, a role that most directors would have filled with an extra, but Seaton had opted against that for a reason. He knew that the people playing the parts of the passengers would be far more highlighted than a typical extra simply walking through a scene in the soft-focused background. He was also aware they would be closely interacting with the film’s stars and would be clearly reacting to the horrific situation they were caught in.

Everyone around me may have thought I was making a mistake by taking that role, but maybe, just maybe, God wasn’t one of them. Maybe all those prayers I had been praying had finally gotten through to Him, and in the mysterious ways in which He liked to work, what seemed like an insignificant role to everyone would prove to be the most pivotal turning point in my career and my life. The characters in that film may have found themselves in a disastrous situation, but for me, landing a role in Airport would prove to be the luckiest airplane ride I would ever take. Had I not gotten that role, the chances are more than good that I would have never been cast in Happy Days, that my lifelong dream would have never come true, and that at this very moment, you would be reading a book by someone other than me.

While everyone had rolled their eyes at my taking the part in Airport,

and while I had no idea that my involvement in that film would prove to be a major stepping-stone toward the big break I had always dreamed of, I really enjoyed working on that production.

Prior to filming, all the actors who were playing the roles of passengers were shown a film about what happens to people when a plane loses pressurization and oxygen. When we actually got on the set, which was the fuselage of a plane, I was positioned two rows in front of the distinguished Academy Award–winning actor Van Heflin, who played the bomber, D. O. Guerrero; and Helen Hayes, who played the stowaway, Ada Quonsett. It was exciting to get to work with someone of Hayes’s stature, even though I had no direct interaction with her. She was, of course, a legend. She had established her career as a performer before I was even born, and had won a Best Actress Academy Award while I was still an Albert Lea toddler.

While I would have loved to have had a role that gave me the chance to really do scenes with members of that impressive cast, I found it to be enjoyable and relaxing just to work with my fellow passengers by doing reactions and to get to know so many of them during what seemed to be quite a bit of downtime between scenes. We would all sit around the set and tell one another stories about our lives, our families, our careers and our hopes. We became a close little group, and it seemed as if each day, the stories being shared brought about more drama—either laughter or tears—than what we were emoting when the cameras were rolling.

One of the actresses, Sandra Gould, who was playing the part of a passenger, became an especially good friend of mine. She was a few years older than me, and her early career had been very similar to mine in that she had done small roles in numerous films and television shows. But unlike the rest of us uncredited passengers, she had landed a role that provided her with regular work and a recognizable face. Her name may not have resonated with the public, but during the time we were shooting Airport, she was also in the midst of what would ultimately be an eight-year run for the hugely popular ABC situation comedy Bewitched. Gould played the part of the shrill-voiced, nosy neighbor Mrs. Gladys Kravitz, and five years after Bewitched was canceled, she reprised the role on the one-season spin-off, the ABC series Tabitha, which starred Lisa Hartman as the grown-up witch daughter of Bewitched’s Samantha and Darrin Stephens.

My Days

My Days